Spring-heeled Jack

The Terror of London

In late 1837, a ripple of panic began to spread around Clapham in South London. Something terrible was lurching out of the fog and attacking local residents.

An elderly lady visiting the cemetery at Clapham was one of the first to see the chilling figure. Clad in a dark cloak, with a hat pulled over its face, she saw it make an ungodly jump over a high fence and disappear into the darkness.

Around the same time, a young girl by the name of Mary Stevens reported an encounter with the same strange character.

Making a giant leap out of a dark alley, it launched a fearsome attack on the girl, ripping at her clothes with its cold, clammy claws. The girl screamed for help and the creature fled.

The next night, a similar figure jumped out at a coach causing it to crash. Several witnesses saw the figure escape the scene by bounding over a 9ft high wall, its high-pitched laughter disappearing into the distance.

Soon, news of the attacks would reach the authorities. Sir John Cowan, the Lord Major, received an anonymous letter alerting him to the spate of attacks. Cowan initially dismissed the letter as wild nonsense.

However, within weeks he was flooded with similar accounts of attacks all across London and was forced to call a public meeting to discuss the crime wave.

News had also started to reach the flourishing tabloid press. Whilst early accounts varied wildly, it was here that Jack’s appearance and modus operandi became fixed, and his famous name - ‘Spring Heeled Jack’ was first born.

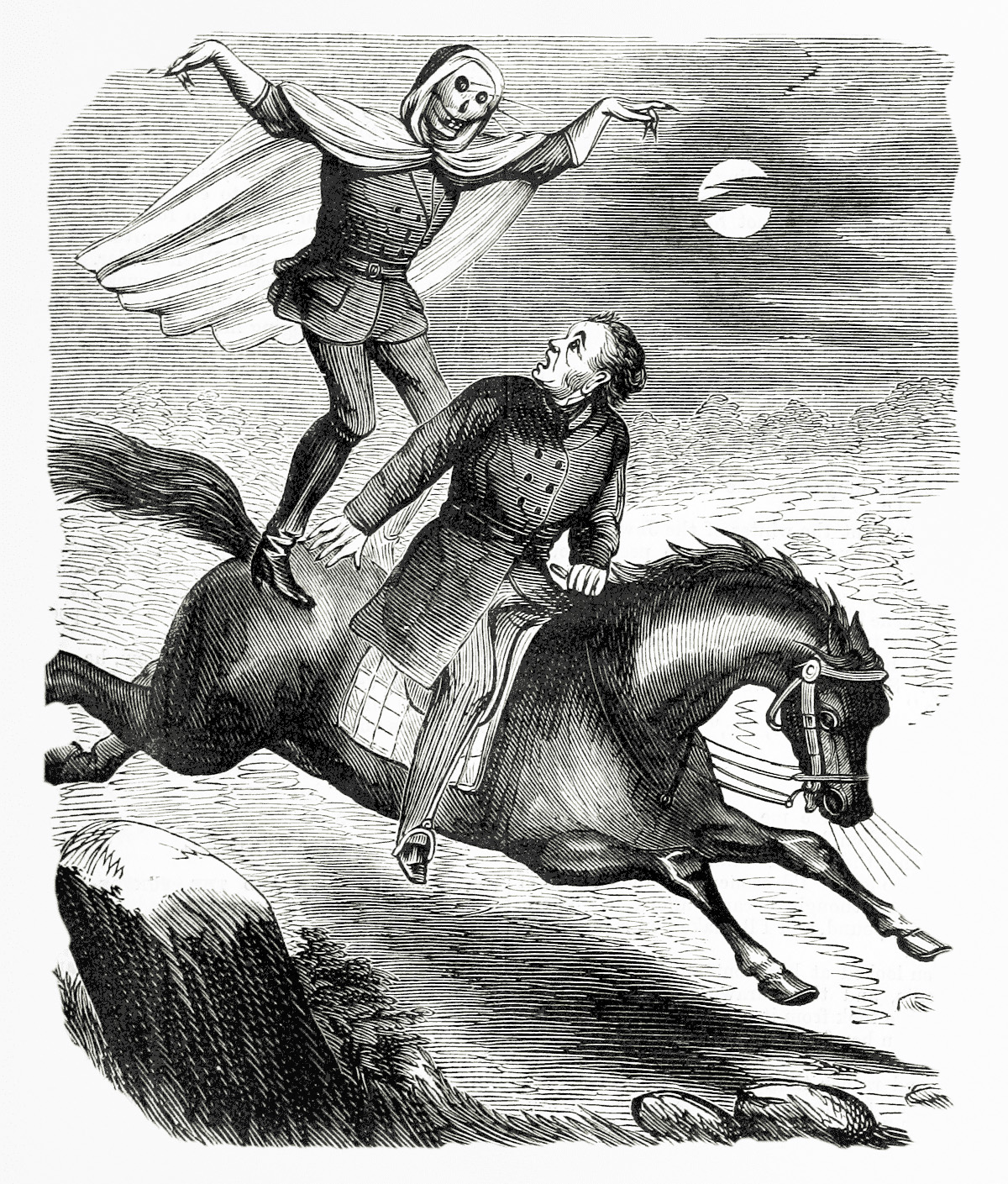

According to the papers, Jack had pointed ears and a hooked nose, fierce claws and glowing red eyes. Beneath a dark cloak, he wore a tight oilskin suit. Always present was his miraculous ability to jump great heights.

By the 1830s, taxation on paper and printing had been greatly reduced, leading to a boom of cheap popular printed media, newspapers and a kind of early graphic novel called the penny dreadful.

These publications were hungry for lurid tales of crime and horror and the stories of Spring Heeled Jack immediately caught their imagination.

It was in the penny dreadfuls that Jack became a kind of early Victorian supervillain, his abilities and appearance massively exaggerated. Now his leaps were over entire building; sometimes he could even fly. His eyes glowed red, and he could spit blue fire from his mouth.

https://theunredacted.com/spring-heeled-jack-the-terror-of-london/

Detection

At about a quarter to nine o’clock… she heard a violent ringing at the gate at the front of the house, and on going to the door to see what was the matter, she saw a man standing outside, of whom she enquired what was the matter, and requested he would not ring so loud.

The person instantly replied that he was a policeman, and said ‘For God’s sake, bring me a light, for we have caught Spring-heeled Jack here in the lane.’

She returned into the house and brought a candle, and handed it to the person, who appeared enveloped in a long cloak, and whom she at first really believed to be a policeman.

The instant she had done so, however, he threw off his outer garment, and applying the lighted candle to his breast, presented a most hideous and frightful appearance, and vomited forth a quantity of blue and white flames from his mouth, and his eyes resembled red balls of fire.

From the hasty glance, which her fright enabled her to get of his person, she observed that he wore a large helmet, and his dress, which appeared to fit him very tight, seemed to her to resemble white oil skin.

Without uttering a sentence, he darted at her, and catching her partly by her dress and the back part of her neck, placed her head under one of his arms, and commenced tearing her gown with his claws, which she was certain were of some metallic substance.

She screamed out as loud as she could for assistance, and by considerable exertion got away from him, and ran towards the house to get in. Her assailant, however, followed her, and caught her on the steps leading to the half-door, when he again used considerable violence, tore her neck and arms with his claws, as well as a quantity of hair from her head; but she was at length rescued from his grasp by one of her sisters.

Miss Alsop added that she had suffered considerably all night from the shock she had sustained, and was then in extreme pain, both from the injury done to her arm, and the wounds and scratches inflicted by the miscreant about her shoulders and neck with his claws or hands.

After this much-reported incident,

James Lea, the 1830s version of Sherlock Holmes got involved in the case.

Lea had solved a couple of high-profile murders, and he was brought in to get to the bottom of all this mess.

It is both silly and a big deal that London authorities called on the biggest name they could think of to solve this case.

Of course, unlike his work on the infamous Red Barn Murder, which had propelled him to fame, this one would prove impossible to solve.

Lea and others believed that Alsop was the victim of a drunken carpenter named Millbank, who denied the crime.

Millbank, who was never formally charged with a crime, was released because the judge believed he was innocent.

Of course, that didn’t matter in 1838 London, because two more attacks had received high-profile recognition by the time the first investigation had been reported in the papers.

So, the truth of that first attack got lost in the hysteria of the next two attacks within that week. And, for whatever reason, there also were no more attacks reported after the end of that week.

Those three reports were the last sightings of Spring-Heeled Jack for over three decades...

https://didyouknowfacts.com/spring-heeled-jack-creepy-clown-batman/3/

Suspects

One theory going round was that the attacks were committed by a bunch of decadent aristocrats for a wager. The idea that the debauched young aristocracy could be a menace to society was a popular one at the time, especially in the working class popular press.

The individual most often mentioned in the press, especially later in the 19th century, was the 3rd Marquis of Waterford, Henry de La Poer Beresford.

Beresford was popularly known as the ‘Mad Marquis’ for his outrageous drunken pranks and antics. He was also in London at the time of the first assaults.

One of the reasons Waterford’s name has cropped up as a suspect was the fact his presence in London coincided with the first Spring Heeled Jack assaults.

The Marquis of Waterford lived in the area of the first attacks in 1837 and 1838, and upon his departure from London in 1842, reports of further Jack sightings dried up.

Waterford returned to Ireland with his new wife and reportedly turned his back on cruel jokes to live a respectable life, until his death in 1859.

Intermittent reports of further Spring Heeled Jack sightings continued after this. If Waterford was responsible for the early attacks, then, as Brewer suggested, these later cases were copy-cats.

The W

One further piece of evidence to suggest the Marquis of Waterford may have been the original Spring Heeled Jack was the reported similarity between a crest spotted on Jack’s chest with Waterford’s coat of arms.

One of Jack’s victims, a young servant boy in a South London household, escaped an encounter with the monster with no more than a fright.

He did, however, allegedly observe an elaborate embroided crest on the assailant’s costume, topped with a letter W.

Could the W have stood for Waterford? Perhaps the Marquis had appropriated an old piece of family garb, complete with crest, to complete his costume?

https://theunredacted.com/spring-heeled-jack-the-terror-of-london/